- Andrei-Carlo Papuc/

- Projects/

- Enhancing autonomous driving: leveraging frame‐based foundation models for improved pedestrian detection and sensor fusion/

Enhancing autonomous driving: leveraging frame‐based foundation models for improved pedestrian detection and sensor fusion

Table of Contents

Course project of Computer Vision by Deep Learning (CS4245)

Authors: Alexandru-Dragos Manolache, Andrei-Carlo Papuc

Introduction #

Autonomous driving refers to the ability of vehicles to navigate roads without the intervention of a human. It relies on a combination of computer vision models (i.e. predictions on RGB cameras) and remote sensing technologies (e.g. LiDAR, RADAR) to allow the vehicle to understand its surroundings, with the goal of outperforming and ultimately replacing humans behind the wheel.

One of the key challenges in autonomous driving is detecting pedestrians with an accurate and reliable method. A computer vision model (e.g. YOLO[1]), trained on driving datasets, is used for creating an initial, slightly inaccurate detection of a 2D bounding box around a pedestrian. Other sensor modalities like LiDAR and RADAR are then employed to improve the bounding box detections, relying on hand-crafted calculations for more accurate region proposals. This method is called sensor fusion and is the general solution emplyed by current self-driving vehicles. Additionally, learned sensor fusion is presented in state of the art methods (e.g. InterFuser[5]), where a transformer model directly learns features from multiple modalities of sensor data.

Generally, models employed on self-driving cars are trained on driving datasets that posses a key features not present in usual datasets like ImageNet[2] and COCO[3]. The visual content differs, there are lots of correlations between consecutive frames, and ultimately they are sampled with additional LiDAR and RADAR data.

Motivation #

Foundational models learn and generalize from large-scale image datasets created by scraping the entire web, meaning driving-related images (e.g. dashcam footage) could be part of the model’s knowledge.

- Segment Anything Model (SAM)[8] is such a model trained on 11 million images and can perform image segmenations with complex point prompts on any image.

- Grounding Dino[6] is another powerful foundational model that performs zero-shot detection using natural language as input.

- YOLO-NAS[7] provides real-time object detection with a neurally optimized architecture.

With current advancements in foundational computer vision models, they could improve sensor fusion pipeline by increasing initial pedestrian detection accuracies and better complement the hand-crafted sensor fusion step.

Main Task #

This blog explores the possibility of using foundational computer vision models for pedestrian detection. It further investigates to what degree pedestrian detection can be improved using either hand-crafted sensor fusion or learned sensor fusion.

Research questions #

This blog aims to answer the following questions:

1. Can foundational models’ implicit knowledge of driving-related images be leveraged for accurately detecting 2D pedestrians?

2. How well do foundational models detect pedestrians in 3D, relative to the autonomous vehicle?

3. How does learned sensor fusion compare to hand-crafted sensor fusion?

4. How suitable are foundational models for real-time use in an autonomous vehicle?

Dataset #

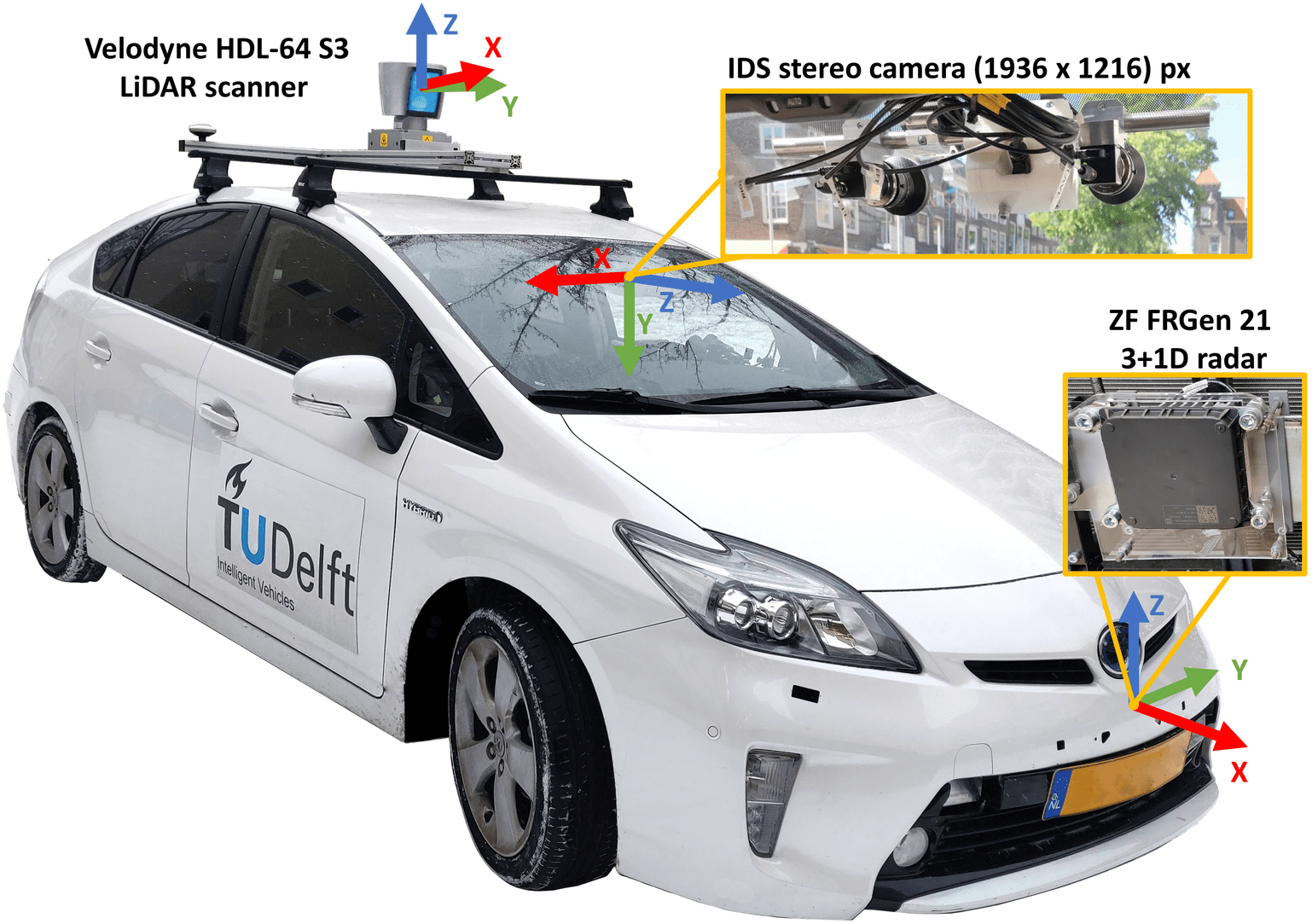

The experiments of this blog use the View-of-Delft[4] (VoD) dataset, a novel automotive dataset recorded in Delft, the Netherlands. It contains image frames with respective LiDAR, stereo camera, RADAR data from urban scenarios, with the sensor setup below.

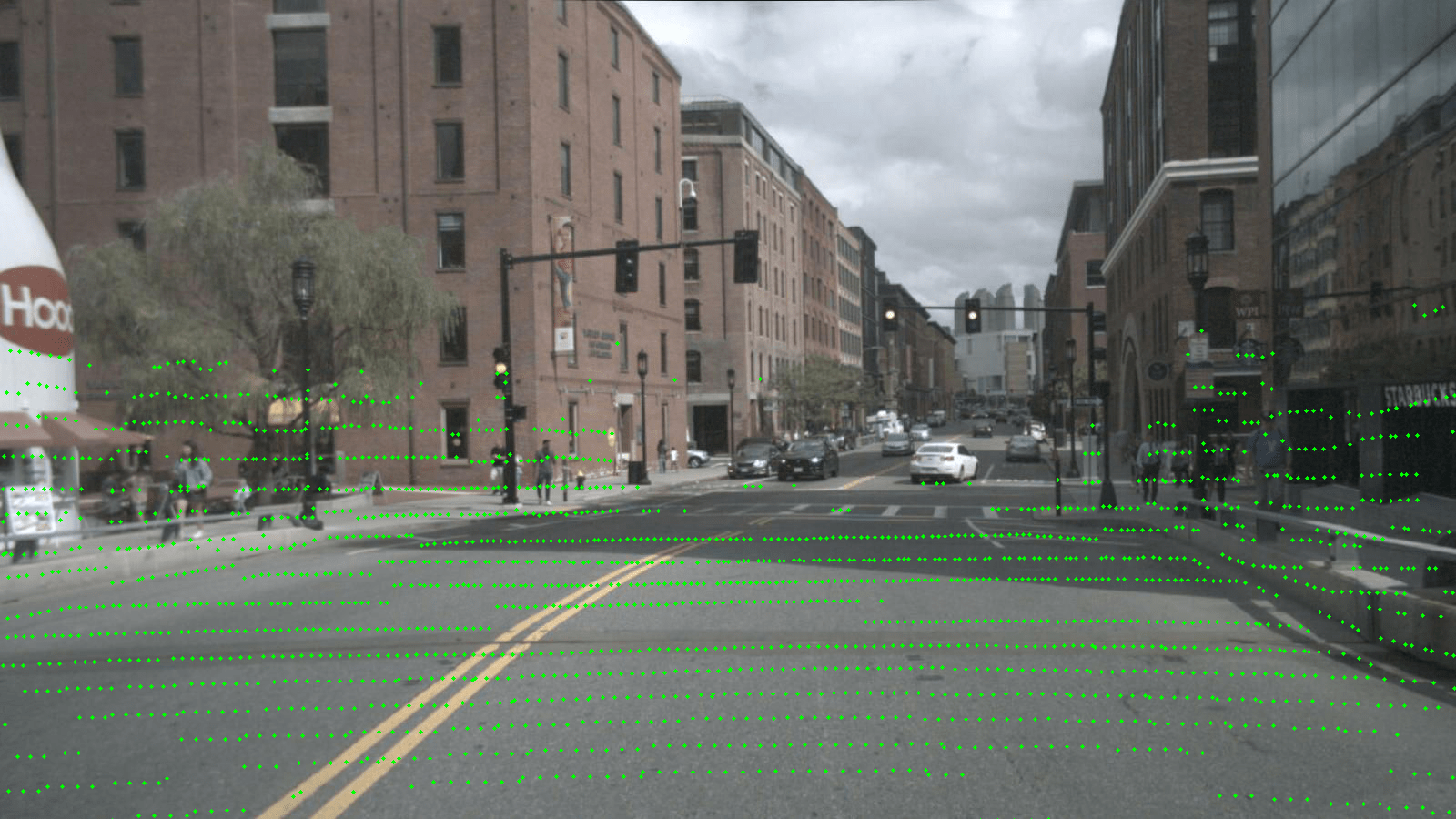

In the figure below LiDAR, RADAR and camera sensing data is projected onto the camera image plane. These three sensing modalities represent the input data available in a typical autonomous vehicle.

The figure below presents the ground truth of the VoD dataset. It contains annotations of 3D bounding boxes for its 14 classes (e.g. pedestrian, cyclist, car, scooter, etc.).

Methodology #

Three methods are presented for detecting pedestrians.

- Monocular vision: uses only a 2D bounding box detector such as YOLO and a few assumptions about width and depth of pedestrians.

- Hand-crafted sensor fusion: a post-processing step in refining the monocular vision results.

- Learned sensor fusion: directly learn features from multiple modalities of sensor data.

Monocular vision #

YOLOv4, Grounding Dino and YOLO-NAS are used for camera only predictions. They are employed separately. YOLOv4 is used as a baseline since it has been widely used in various studies and solutions, hence a variety of performance metrics and benchmarks for it are present. Grounding Dino and YOLO-NAS are two foundational models that perform object detection. They have been trained on large-scale datasets that include images from the entire internet. As such, their knowledge and abilities are tested against a more specific baseline. For our experiments YOLO-NAS is fine-tuned on VoD, while YOLOv4 and Grounding Dino are utilized without any modifications.

The models’ output is a 2D bounding box which is translated to 3D with the following two assumptions:

- bounding boxes in 3D assume equal width and depth

- a fixed ground plane model is used to intersect the 2D bounding boxes bottom center with the plane, in order to get 3D locations

More specifically, to obtain the bounding boxes in 3D, a transformation from uv coordinates to normalised coordinates in the camera frame is performed. The 3D light ray is intersected with the assumed ground plane in the camera frame.

Hand-crafted sensor fusion #

Object detection foundational models have the disadvantage that they generate bounding boxes with variable aspect ratios. Thus, sizes of bounding boxes do not relate directly to the distance in the physical world, but are affected by the apparent object size in the image. This in turn affects the projection to 3D in the monocular vision case.

By making use of additional sensing modalities, a couple of improvements can be made, specifically for the projection of the 2D bounding boxes to 3D. The following algorithm is proposed.

- Extract LiDAR and RADAR points and transform them to the camera frame. In this step we also perform ground removal segmentation for the lidar point cloud using the open3D package.

- Filter out points in both point clouds that lie behind the camera. Project remaining LiDAR and RADAR points on the camera image.

The following image contains projected LiDAR, RADAR and monocular bounding box results. Green points represent LiDAR data, with the points belonging to the ground plane filtered out. RADAR points are colored by their respective radial velocities in m/s, where a white dot means a magnitude of zero. A blue point point represents a negative radial velocity. A red point means a positive radial velocity, meaning the object is moving away from the camera.

Learned sensor fusion #

This approach utilises VoxelNext[9], a fully-sparse 3D object detector that predicts objects directly upon sparse voxel features. This prediction pipeline feeds a YOLO-NAS bounding box detection as a prompt to Segment Anything Model (SAM), which creates an accurate segmentation mask. The mask is used as a filter on LiDAR data to select relevant points and further detect the 3D bounding box with VoxelNext.

Experiments #

With current advancements in foundational computer vision models, the experiments of this section explore the possibility of using foundational computer vision models for pedestrian detection, as well as to what degree pedestrian detection can be improved using either hand-crafted sensor fusion or learned sensor fusion.

Two evaluation scenarios are considered. The 2D camera projection view evaluates the 2D localization accuracy, while birds eye view (BEV) quantifies the accuracy with regards to the detection position in 3D space.

The following metrics are used to evaluate the performance of object detections:

- Intersection over Union (IoU) quantifies the overlap between the predicted bounding box (detection) and the ground truth bounding box (annotation) of an object.

mean Average Precision (mAP) measures the accuracy and robustness of an object detection algorithm across different IoU thresholds. The greater the intersection between the two bounding boxes (prediction vs ground truth), the greater the area under the Precision-Recall curve, which represents the Average Precision (AP) score. An AP is calculated for all IoU thresholds and then all scores are averaged to determine the mean Average Precision (mAP) score.

mAP for birds eye view (BEV) considers the 2D center distance on the ground plane rather than intersection over union based affinities. Specifically, the predictions are matched with the ground truth objects that have the smallest center-distance up to a certain threshold. For given match thresholds of

{0.5, 1, 2, 4}meters AP is calculated by integrating the recall vs precision curve. These are averaged to compute the mAP.

The research questions are discussed next.

Can foundational models’ implicit knowledge of driving-related images be leveraged for accurately detecting 2D pedestrians? #

The expectation is that YOLO-NAS with sensor fusion performs best, since it adds a post-processing step to improve monocular vision.

However, the visualisation and the table below show YOLO-NAS monocular is the best performing model for the 2D detection scenario, scoring ~16 more than the baseline and ~3 more than its sensor fusion (s.f.) variant. The lower mAP of s.f. variant is due to the hand crafted rules for selecting relevant LiDAR and RADAR points on pedestrians (steps 4 and 5 of the hand-crafted sensor fusion algorithm presented before).

At first, it tracks pedestrians well, but can confuse them with objects that are moving fast inside the 2D bounding box containing the pedestrian. For example, a car or a moped could be contained by the bounding box, but moving in the background. As a result, the bounding boxes are removed since the detection now has a high radial velocity.

YOLO-NAS is fine-tuned on this specific dataset and performs best. In contrast, Grounding Dino has not been finetuned and scores ~7 more points than the baseline. These results show foundational models do not necessarily need adapting to a autonomous driving dataset for accurate pedestrian predictions in 2D.

| Model | mAP (monocular) | mAP (s.f.) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (YOLOv4) | 30.1 | 30.9 |

| Grounding Dino | 37.1 | 38.1 |

| YOLO-NAS | 46.1 | 42.6 |

How well do foundational models detect pedestrians in 3D, relative to the autonomous vehicle? #

The birds’ eye view perspective illustrates the 3D bounding boxes centers relative to ground truth. By observing the scene from above, bird’s eye view enables accurate localization of objects in the 2D plane. This is particularly useful for detecting and tracking objects on the road, such as vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists. The top-down view helps to mitigate occlusion issues that can occur with traditional camera views, where objects can be hidden or partially obscured by other objects.

Birds’ eye view plays an important role in autonomous driving as it assesses how accurate is the depth perception of an autonomous vehicle.

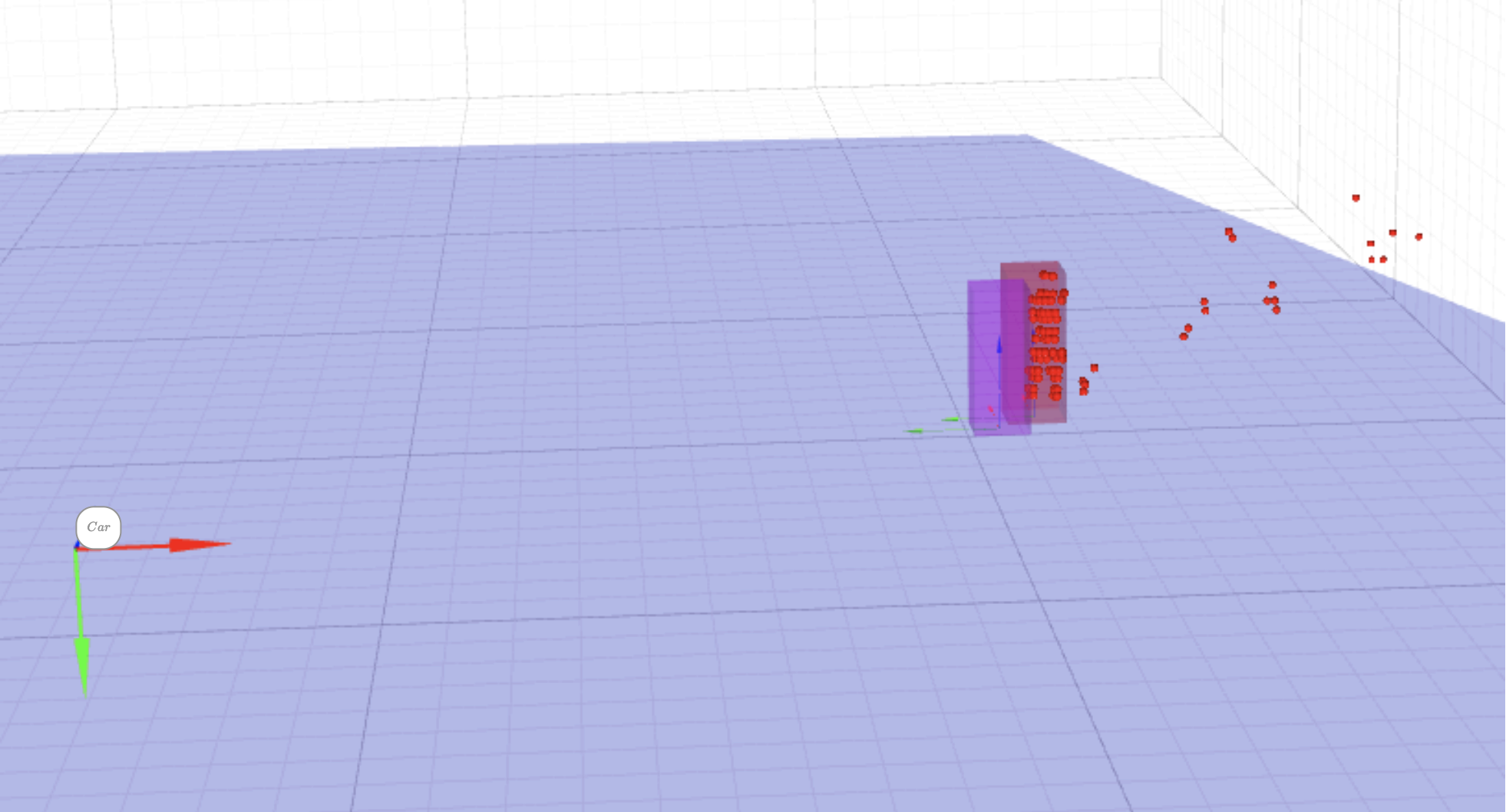

This experiment shows Grounding Dino monocular and YOLO-NAS with s.f. as best performing in their categories. The big increase of mAP from monocular to s.f. is because of the inaccurate initial bounding boxes with regards to the ground plane. Sensor fusion corrects them and thus shifts the center more towards the ground truth using LiDAR information. The figure below show the ground truth pedestrians relative to the car moving forward.

| Model | mAP (monocular BEV) | mAP (s.f. BEV) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (YOLOv4) | 31.4 | 48 |

| Grounding Dino | 33.9 | 54.5 |

| YOLO-NAS | 29.7 | 65.1 |

How does learned sensor fusion compare to hand-crafted sensor fusion? #

The previous experiments showed how hand-crafted sensor fusion can lead to unexpected erros if the processing steps do not cover all possible scenarios. Learned sensor (SAM + VoxelNext in table below) fusion should perform better since the model sees multiple sensor modalities at once, eliminating the hard-coded decision steps.

Surprisingly, the results of SAM and VoxelNext method in the table below achieve significantly lower mAP than other methods. VoxelNext has been trained on the NuScenes dataset which was recorded on a different continent. The model could have needed fine-tuning on VoD to achieve relevant results. This shows that learned sensor fusion methods might not easily generalise to other datasets when they differ both in sensor packages and region.

| Model | mAP (s.f.) | mAP (s.f. BEV) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (YOLOv4) | 30.9 | 48 |

| Grounding Dino | 38.1 | 54.5 |

| YOLO-NAS | 42.6 | 65.1 |

| SAM + VoxelNext | 3.8 | 4.6 |

How suitable are foundational models for real-time use in an autonomous vehicle? #

In the autonomous driving world, fast object detection allows for timely decision-making, adaptive control, and handling of complex environments with multiple moving objects. In emergency situations, real-time object detection is crucial for the vehicle to react promptly and minimize the risk of accidents.

A typical sensor measurement update of LiDAR + monocular vision is about 10 Hz. Meaning, an ideal pedestrian detector would be able to detect all pedestrians under 0.1 [s].

The table below shows average time for each method proposed in particular. It’s important to mention that all proposed methods were run on the CPU. The larger the foundational model, the longer inference can take, and this is visible in the table below. Even though foundational models are able to generate accurate detections both in 2D and 3D, these would not be ideal for real-time use.

| Model | monocular avg. time [s] | sensor fusion avg. time [s] |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (YOLOv4) | 0.79 | 1.43 |

| Grounding Dino | 12.67 | 12.87 |

| YOLO-NAS | 4.52 | 4.85 |

| SAM + VoxelNext | N/A | 40.41 |

Conclusion #

This blog explores the potential of foundational computer vision models to improve pedestrian detection and sensor fusion in the autonomous driving domain. The following conclusions are drawn:

- Foundational models’ implicit knowledge of driving-related images can be leveraged for accurately detecting pedestrians, but hand-crafted sensor fusion can hinder their performance in 2D.

- They detect pedestrians in 3D better than a YOLOv4 baseline thanks to sensor fusion.

- Learned sensor fusion methods do not easily generalise to other datasets as they differ both in sensor packages and region.

- Inference time speed-up on CPUs is needed for large-scale deployment.

Our results are fully reproducible using our code on GitHub. Moreover, to successfully reproduce our results you must first request academic/research use for the View-of-Delft dataset here.

Discussion and Future Work #

Due to time limitations, some answers to the proposed researched questions could’ve been further motivated. To do so, additional work could’ve been done in the following areas:

- Fine tuning VoxelNext model on View-of-Delft dataset. VoxelNext was trained on the NuScenes dataset, with the same sensing modalities available as in the VoD dataset. However, the LiDAR sensor differs significantly. We believe this is the one of the main causes which affects the mAP results of learned sensor fusion. The dataset used in this blog also contains data recorded on a different continent, which might be non-representative to the data used to train VoxelNext. The figure below shows the LiDAR data differences between the two datasets.

NUSCENES sample image with LiDAR (left), VoD sample image with LiDAR (right)

For the fourth research question assessing the aplicability of models in real-time, results were only using CPU computation. Running inference of the large foundational models using dedicated GPUs would favor the foundational models more in terms of runtime per sample. Some autonomous vehicles are equipped with dedicated GPUs.

Testing multiple learned sensor fusion methods can give a better picture of the overall comparison. PointPillars[10] uses semantic segmentation and LiDAR sensing data to extract better 3D detections. Of course limitations arise for sparse lidar point areas such as far away regions from the camera.

References #

[1] Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R., & Farhadi, A. (2016). You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 779-788).

[2] Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L.-J., Li, K., & Fei-Fei, L. (2009). Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 248–255).

[3] Lin, T. Y., Maire, M., Belongie, S., Hays, J., Perona, P., Ramanan, D., … & Zitnick, C. L. (2014). Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13 (pp. 740-755). Springer International Publishing.

[4] A. Palffy, E. Pool, S. Baratam, J. F. P. Kooij and D. M. Gavrila, “Multi-Class Road User Detection With 3+1D Radar in the View-of-Delft Dataset,” in IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 4961-4968, April 2022, doi: 10.1109/LRA.2022.3147324.

[5] Shao, H., Wang, L., Chen, R., Li, H., & Liu, Y. (2023, March). Safety-enhanced autonomous driving using interpretable sensor fusion transformer. In Conference on Robot Learning (pp. 726-737). PMLR.

[6] Liu, S., Zeng, Z., Ren, T., Li, F., Zhang, H., Yang, J., … & Zhang, L. (2023). Grounding dino: Marrying dino with grounded pre-training for open-set object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.05499.

[7] Aharon, S., Louis-Dupont, Ofri Masad, Yurkova, K., Lotem Fridman, Lkdci, Khvedchenya, E., Rubin, R., Bagrov, N., Tymchenko, B., Keren, T., Zhilko, A., & Eran-Deci. (2021). Super-Gradients.

[8] Kirillov, A., Mintun, E., Ravi, N., Mao, H., Rolland, C., Gustafson, L., … & Girshick, R. (2023). Segment anything. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.02643.

[9] Chen, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, X., Qi, X., & Jia, J. (2023). Voxelnext: Fully sparse voxelnet for 3d object detection and tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 21674-21683).

[10] Lang, A. H., Vora, S., Caesar, H., Zhou, L., Yang, J., & Beijbom, O. (2019). Pointpillars: Fast encoders for object detection from point clouds. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 12697-12705).